This stretch gate looks like any of its kind in any landscape where livestock need to be kept in or out and where people do not have the means or inclination to invest in a more substantial barrier. This gate is in southern Sonora, Mexico, in the Municipio of Alamos.

We have been passing through it for more than twenty years. Maybe not this exact gate, but some version of it. The tensile stress of repeatedly opening, dragging, and stretching a stretch gate causes wear and tear on its materials, especially the tree branches that serve as pickets. These are easily and affordably replaced. It just requires the knowhow to wire the pieces together and to not get nicked on the barbed wire in the process. Stretch gates cause a certain amount of wear and tear on the people who open and close them.

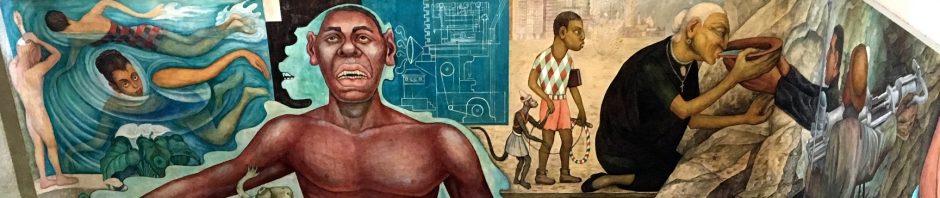

In the photo above, taken on December 10, 2023, Don Ángel Esquer, 92 years old, is closing the stretch gate at the end of an overnight trip we took with him.

The road ahead goes through cattle pastures and thorn-scrub woodlands then begins to climb up into the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental, becoming rockier and gnarlier as it ascends. The landscape becomes wilder, the scraggly vegetation giving way to galleries of columnar cactus, giant fig trees, oaks, pines, and palms. The vistas extend across multiple ranges of mountains to a faraway horizon. In places it passes along sheer cliffs falling into shadowy barrancas. The road ends at Rancho Santa Barbara. It was our destination with Don Ángel.

In the United States, an equivalent landscape might well have the status of National Park or Wilderness Area. The entry would be well marked. There would be a kiosk with informational maps and checklists, if not a visitor’s center and gift shop. There would be tourists with cellphones.

Here, there is just a stretch gate.

I think of the gate as my secret passage. It is quite possible that sooner or later multitudes of people with discretionary incomes – tourists, in other words – will discover what lies beyond the gate. I have no control over this possible future. I am an interloper of sorts myself.

As recently as fifty years ago these parts were populated with ranches and small communities. This road and others crisscrossing the Sierra formed a network well-traveled by cattlemen and their families, tradespeople, and folks on the move, on foot or beast of burden, mule, burro, horse. Today the rugged landscape is mostly absent of people. They have moved away to the city of Alamos or beyond for work, education, medical care, electricity, connectivity, cold beer, to find a partner and make a family, to leave behind the body-breaking, slim-profit-margin life of ranching, to acquire some measure of comfort and modernity.

It is silent out here now except for birds, breezes in the trees, jets flying over, a cow bell, the chance braying of a burro.

Don Ángel is our primary source for stories about this landscape which he knows like the back of his work-worn hand. He was born on Ranchito El Saucillo in the Río Mayo watershed, which drains to the north and west off the steep inclines of this stretch of the Sierra. He married María Ramirez Vega, who grew up on another small ranch at Arroyo Citorijaqui in the Río Cuchujaqui drainage which cuts its downward path to the south. These two river systems have etched deep arroyos in the Sierra. This pattern of erosion has determined the system of roads and trails used by people, while the seasonality and location of surface and ground water have governed the planting of crops and management of livestock. Geology creates landscapes which shape the behaviors of humans. In turn, humans, during their short tenure on the planet, alter the landscape to meet their needs and designs. All landscapes are in limbo.

Rancho Santa Barbara is tucked in the Sierra between these two river drainages. Four generations of the Alvarez family have lived and made a living here. The current members of the family still work cattle and grow corn and frijoles. They come and go, often staying for days or weeks, but no one lives here all the time. I understand the ties of custom, the economic incentives much less so. Don Ángel spent a lot of time here as a young man. His sister and only sibling, Ramona, married Gaspar Alvarez. The ranch is packed with memories for Don Ángel. He remembers, for instance, the day when Gaspar, quite a bit older, laid eyes on sixteen-year-old Ramona and made known his plans to marry her.

We intend to take Don Ángel up to Santa Barbara until we can’t. There are eight gates along the way to open and close. Some are metal, some are stretch. Don Ángel and I will take turns opening them until we can’t. This stretch gate – the first to open, the last to close – I hold special because I know where the road leads.

You must be logged in to post a comment.