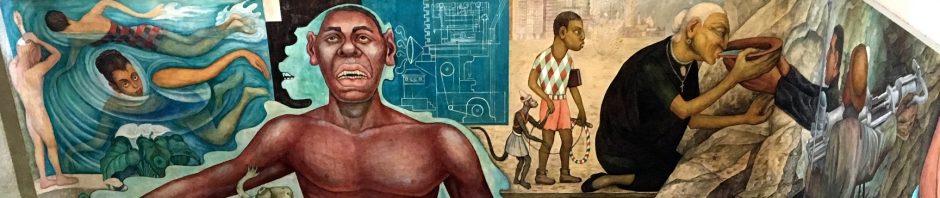

Bornean Stubtail (Urosphena whiteheadi)

Photo by David Smith

The Bornean Stubtail is a plain brown bird about the size of a goose egg. What passes for its song consists of rapid outbursts of high-pitched static. As its name implies, it is found only on the island of Borneo and it doesn’t have much in the way of a tail. There are far more stunning and easier-to-see birds in Borneo, but the Stubtail is the sly hermit messenger who renders best what twenty days’ birding in the tropical forests of Sabah1 meant to me.

I estimate I saw the Bornean Stubtail for no more than three seconds. As much as I might pretend otherwise, I am not likely to ever see one again. It was darting from twig to twig in the tangled understory of the fog-shrouded forest, responding to playback of its song. A tiny nutmeg-brown bird, cream-colored eyebrow, dark sparkly eyes, flesh-pink toothpick legs, no tail to speak of. There it was, then there it wasn’t.

My few seconds of Bornean Stubtail contained compressed memories of other reclusive brown birds—Swainson’s Warbler in Texas, Winter Wren, Veery, and Hermit Thrush in the woodlands and bogs on our farm in Minnesota, Brown-backed Solitaire in Mexico. These are birds that, with the possible exception of the warbler, I will see on many more occasions unless I fall over dead tomorrow. Henceforth when I see them, they will remind me of my one and only Stubtail.

We saw the Bornean Stubtail at Mt. Kinabalu National Park2, on our fifth and final morning in the park and our last day of birding in Sabah before heading back to Kota Kinabalu3 where we would scatter the next day to our various homes and routines in temperate North America. We were a party of eleven—eight participants and three guides, who on our final morning were bearing the professional onus of having to produce for the group four Bornean endemics, one of them the Stubtail, all uncommon and difficult to coax into view. 4

Birding in Borneo is richly rewarding, hard work, and for a first (perhaps only) timer on the island sensorially overwhelming. There are roughly 650 species of birds of which 420 are resident and of that number 50 or so are endemic to the island; the other 130 species are migrants or winterers from nearby continents. Many of these birds are taxonomically grouped in Asian, Australian, and African families unfamiliar to birders who have not ventured out of the Western Hemisphere. Bulbuls, babblers, barbets, broadbills, bee-eaters, pittas, hornbills, sunbirds, spiderhunters, flowerpeckers. It is head spinning.

Competing with the birds for attention is everything else, which in Borneo is a great deal (and I focus narrowly on non-human diversity while omitting the rich histories, religions, cuisines, and cultures of Malaysia and its surrounding Southeast Asian neighbors): 14 primates, including Orang Utan; more than 280 mammals, including flying squirrels ranging in size from 5 inches to 3 feet, the Bearded Pig, the Bornean Pygmy Elephant, 27 species of whales and porpoises, and 94 species of bats; who knows how many invertebrates, including the world’s second-largest insect (Phoebiticus chani, a giant stick insect measuring 56.7 cm 5); and an equatorial explosion of floral diversity—an estimated 10,000-15,000 flowering plants—including the world’s largest flower (Rafflesia, which can measure 1 meter across), perhaps as many as 3,000 species of orchids, 500 ferns, and 3,000 species of trees, which include some of the tallest trees on the planet. It is hard to describe Borneo. The inventories of species blur, the superlatives begin to sound trite, the describer starts to run out of oxygen.

Old female Orang Utan (Pongo pygmaeus) on roof of a building at Gomantong Caves.

Photo by Suzanne Winckler

Rafflesia keithi at the Viviane Rafflesia Garden near Poring Hot Springs.

Photo by Suzanne Winckler

At the four forest preserves we visited in Sabah we had the realistic potential of seeing about half of the island’s 650 birds. I tell myself that if I lived in Borneo—even for just six months—I could with patience and repeated effort have found a fair number of these birds by myself. We had twenty days. We were in the hands of professionals whose business and passion (I do not use the word lightly) is to find birds and show them to other people.

It is hard to explain to non-birders the level of expertise, physical dexterity and endurance, sensory acuity, and depth of knowledge required to be a professional bird guide. To non-birders, all birders look alike—people in drab clothing rambling in the forest craning their necks. Bird guides are professional athletes who look superficially like ordinary people and, as long as their stamina, vision, and hearing hold up, they do not peak in their 30s or 40s like many professional athletes. One of our Borneo guides, Rose Ann Rowlett, who happens to be one of my oldest and dearest friends, is 70. She is a lithe and beautiful specimen of a professional bird guide.

A synopsis of our bird guides at work: Using playback requires amassing recordings, which the guide has made him or herself or acquired from another professional guide or a source like xeno-canto 6, and then cuing up a specific song in a matter of seconds. It is essential to already know the songs and calls because it helps a guide pinpoint the general location of a bird and then do playback to draw it in. Bird guides, depending on how widely they lead tours, typically have knowledge of several hundred to several thousand birdsongs. In Borneo, extremely reclusive birds, of which there are many, respond very slowly to playback, especially during the non-breeding season when there is less incentive to protect territory. Often, we sat quietly for 30 minutes to an hour on a trail while Rose Ann did playback. If the bird came into view (sometimes it did not), our guides then began the art of showing the bird to us. Rose Ann, Richard Webster, and our in-country guides Hazwan bin Suban and Napoleon Dumas used green lasers to point out a bird’s perch, which requires great skill to aim the light below or to the side of the bird so as not to disturb it. Richard, Hazwan, and Napoleon typically were in charge of getting telescopes on birds within seconds for closer views. All of this action took place as quietly as possible (a lot of whispering and gesturing) on narrow and often steep and slippery trails.

Napoleon Dumas and Rose Ann Rowlett on the Hornbill Trail at Borneo Rainforest Lodge, working on three shy birds, Blue-headed Pitta, Bornean Banded Pitta, and Bornean Ground-Cuckoo.

Photo by Suzanne Winckler

So back to our last morning birding in Borneo. We started out in our big tour bus at 5:30 a.m. before sunrise. At the time, in the under-caffeinated mental haze of predawn, I did not fully appreciate how intent Rose Ann, Richard, and Hazwan were on finding those four endemics. The first objective was Everett’s Thrush. Like the Stubtail, it is a diminutive brown bird but ever so slightly less reclusive. It regularly comes out in the open if only briefly and in the dark to forage before dawn in the leaf litter along the shoulders of the main road through the park. At approximately 6 a.m., we saw—i.e., we were shown—two individuals tossing leaves on the side of the road in the glow of the bus’s headlights. Under the circumstances, as I crouched in the aisle of the bus and peered through my binoculars through the windshield to the circle of light in the pitch dark, the birds seemed to me more like a dream than a reality. The Everett’s Thrush was a lifer7 for all the participants and for Hazwan, who has been leading tours in Borneo for a dozen years—an indication of what a rare and challenging bird it is to see.

Our last morning on the Mempening Trail at Mt. Kinabalu Park.

Photo by Suzanne Winckler

About 20 minutes later—at 6:20 a.m. according to my notes—we were out of the bus and walking as quietly as eleven people can through the forest on the narrow Mempening Trail as Rose Ann worked to coax Crimson-headed Partridge into view by playing its loud, repetitive, almost frantic-sounding call over and over. It is one of the most common and distinctive sounds of Mt. Kinabalu. We heard them every day of our stay in the park but had yet to see one. (I will say parenthetically but emphatically that the sounds of birds in Borneo are as wonderful as the visions of them.) Two were responding—these partridges engage in dueting—to Rose Ann, seeming to be moving closer and closer. At 6:35 a.m. a pair sidled across the narrow trail just slowly enough for us to see their endearing partridge plumpness and stunningly red head and breast. Birds seen in the early morning light filtering through the forest almost seem to glow.

Two for four. We broke for breakfast.

At 8:45 a.m. with about two hours to bird before heading to Kota Kinabalu, we drove back up the park road in a last-ditch effort for the two other endemics: Fruithunter and Bornean Stubtail. The day before, birding along the road, Rose Ann, Richard, and Hazwan had heard the thin, quavering, high-pitched call of the Fruithunter—an implausibly feeble vocalization for a rather large (22.5 cm) bird. At 9:05 a.m., as we were walking down the road, our guides heard and found two Fruithunters, which were seen by most of the party but not me. 8 Shortly, there was a flurry of excitement as Rose Ann called in the Bornean Stubtail to a tangle of brush by the side of the road. I was barely processing my glorious three seconds of Stubtail when our guides got one of the Fruithunters back in the telescopes. This one I saw—a plush bird with tuxedo-trim markings of gray, buff, and black.

Four for four.

Rose Ann Rowlett and Hazwan bin Suban listening for the Fruithunter (Chlamydochaera jefferyi) on the road at Mt. Kinabalu Park.

Photo by Suzanne Winckler

What made our last morning birding in Borneo so extraordinary was not just seeing four reclusive endemics in the space of a few hours but watching our guides working to find and show them to us. It had all the elegance and intensity of a perfect game.

And then the game is over. We birded down the road for another hour, performed the various mundane tasks of checking-out of our accommodations, like paying our laundry bills, ate a tasty Chinese lunch at Rose Cabin, a small hotel just outside Mt. Kinabalu Park, and then our bus was rolling down the highway to Kota Kinabalu. We were homeward bound and I had a sly hermit messenger in my pocket.

Footnotes

1 Sabah is one of the two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo (Sarawak is the other). Sabah has the poetic Malaysian nickname of Negeri Di Bawah Bayu—Land Below the Wind—a reference to its (and Borneo’s) latitude below the zone of tropical typhoons. We visited four conservation areas—three in the lowlands (Sepilok Rainforest Discovery Center and Forest Preserve, Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary and Sukau Rainforest Lodge, and the Danum Valley Conservation Area and Borneo Rainforest Lodge) and one montane area in the Crocker Range (Mt. Kinabalu National Park). Outside of forest preserves large portions of Borneo’s lowlands have been converted to oil palm plantations while the foothills are agricultural areas for vegetables and fruit.

2 Mt. Kinabalu National Park is a spectacularly beautiful World Heritage Site situated in the Crocker Range and encompassing Mt. Kinabalu (13,438 feet), the highest mountain in the Malay Archipelago and a pilgrimage for people who hike the peak with the goal of witnessing the sunrise from the summit. The plant (e.g., 800 species of orchids), avian (326 species), and mammalian diversity is phenomenal. There is a great trail system, gorgeous vistas, comfortable lodging, and the climate (mean temperatures between 70F – low 80F) provides quite a contrast to birding in the steamy lowland forests. Although as a native Texan I rather enjoyed the steamy lowlands.

3 Kota Kinabalu (population about 450,000) is the capital of Sabah located in northern Borneo. It is a sophisticated, friendly, bustling port city on the South China Sea with great vegetable, fruit, meat, and fish markets, and ethnic and cultural diversity of which I would like to be a part.

4 For non-birders: the standard method for getting birds to come into view is to do playback of their songs and calls. Additionally, guides sometimes use playback of diurnal owls, which can agitate birds and cause them to fly toward the sound and thence into better view. Playback is widely debated in the bird watching community; bird-guide writer and artist David Sibley has a useful essay on the proper use of playback. See: http://www.sibleyguides.com/2011/04/the-proper-use-of-playback-in-birding/. For obvious ethical reasons, playback is prohibited in places where hundreds of birders come to see a rare bird for a particular location and/or season (e.g., Elegant Trogons in Cave Creek Canyon in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeast Arizona).

5 It was the world’s largest insect, until this year (2016), when Phryganistria chinensis (62.5 cm) was discovered and described from China. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phobaeticus_chani and http://www.popsci.com/introducing-worlds-longest-insect

6 xeno-canto is an open-source website for sharing recordings of wild bird sounds from around the world: http://www.xeno-canto.org.

7 For non-birders: a lifer is a bird seen for the first time in one’s life.

8 The dynamics of a participant on a birding trip not seeing a bird are complex. I feel badly in the moment for the guide who is trying to show it to me and a little frustrated and embarrassed with my inability to see it. But not seeing a bird, even if it is my last chance to see it, is not ultimately disappointing to me. Perhaps this makes me not a genuine birder. I figure it was not meant to be and in a few moments, hours, or the next day, I will see or hear another bird that will bring me great joy.

Final note: Use of anthropomorphic terms

I am aware of the pitfalls of using anthropomorphic terms when describing or talking about non-human organisms. When I am in the company of biologists talking about their research of non-human organisms (or with non-biologist friends who like me have an interest in scientific topics like evolution and animal behavior), I understand and agree that the rules of the conversation restrict the use of anthropomorphisms. In casual non-scientific contexts—watching birds, for instance—I believe it is justified and inevitable to use human-centric adjectives, similes, and metaphors to describe perceived qualities of the non-human organism or more frequently our human response to the non-human. Even in casual contexts, I make an effort to restrain my use of anthropomorphic terms simply because layer upon layer of humanoid descriptors can quickly become cloying, like the frosting on a store-bought cake. But I am human and human language is all I have to work with when I see and describe the world. So I anthropomorphize from time to time. Some readers may wince or raise an eyebrow with “sly hermit messenger” or “endearing partridge plumpness.” I don’t think the Bornean Stubtail as a species is “sly”—rather I mean the one Stubtail I saw cleverly made me think about birding in Borneo in a way I might not have had I not seen it. I cannot deny, I find small, reclusive, plump partridges to be endearing, especially when observed going about their non-human business largely oblivious of me. I suppose if I were taking a Crimson-headed Partridge out of a mist net and it seized my finger in its vise-like beak, I might feel otherwise.

You must be logged in to post a comment.