Today we went out to the cemetery at Rancho Tlacuachi with Leobarda and her two grandchildren Guadalupe and Rogelio. It is Día de los Muertos. We’ve been to the cemetery several times with her but never on this day.

When we got there, we saw that the cemetery had been cleaned and all the graves dusted and decorated with flowers, fresh and fake, as well as candles called velas. The place almost seemed to luminesce.

Leobarda, the children, and David set to work adding more flowers and candles to her family’s graves – her brother, mother, father, some siblings who died young. I watched. Another family arrived in a pickup truck.

A wisp of a man in tattered clothes with about four teeth in his mouth appeared as if from thin air. Leobarda knew him – and, for that matter, everyone else who was there. He lives at a nearby ranch and is the current caretaker of the cemetery. His name is something like Raimundo. His nickname, no surprise, is Mundo. I assume he did the tidying up (or supervised it), and there must be some cemetery fund for purchasing the flowers and velas. We laughed with him. He went to join the other families in a shady spot where he sat on his haunches with a Tecate and cigarette. Off and on, he would mill around talking to folks and straightening flowers on graves.

I went to look at the newest grave, still with mounds of dirt around it. The date of death was October 24th, and the age of man interred was 35. I shuddered. I asked a woman Leobarda had been talking to if she knew what happened. She put her hand around her throat. He had committed suicide leaving five children and a wife. He was from her same village.

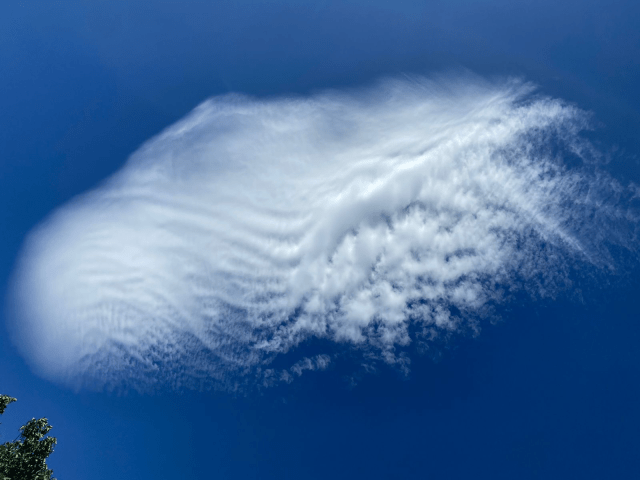

Several more families arrived and went to work around the graves of their departed ones. It is always striking to me, coming from a city, how quiet the campo is. Just the breeze and murmur of people talking and laughing.

The breeze, though slight, kept blowing out the velas, and Leobarda and her grandchildren spent a fair amount of time relighting them. The wind would extinguish a certain portion again. We don’t want the candles to go out. We don’t want the people we love to die. I suspect over the afternoon and evening, more people came, and tonight, in the dark, perhaps a few candles will still flicker in the cemetery at Rancho Tlacuachi.

You must be logged in to post a comment.